By: Amanda Guarragi

In the 1700s, the religious community known as “The Shakers” originated in England. It is a sector of Protestant Christians. They were formally known as “The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing,” and eventually moved to the United States in 1774. A woman named Ann Lee led the community through their hardships.

They believed in the dual nature of God (male and female), the pursuit of a heavenly community on Earth and ecstatic worship (shaking, quaking, singing, dancing and speaking in tongues as the Holy Spirit entered their bodies). They promoted gender equality and separated themselves from the rest of the villages because they believed their commune was built through God.

Mona Fastvold’s The Testament of Ann Lee explores the nature of female agency through religious duty in three stages of life. Ann Lee (Amanda Seyfried) was lost early in her life and found the Shaker Movement.

She found comfort in this community with her younger brother, William Lee (Lewis Pullman), because it reinforced her belief in a higher power and brought her closer to understanding the world around her. The most powerful aspect of faith is believing that there is a reason for everything that happens. A spirituality that connects the individual with an ethereal energy that can explain an unprecedented event.

The uniqueness of the Shaker Movement lies in the physicality they bring to worshiping God. Fastvold linked the musicality of hymns and physical expression so beautifully, making them appear kinetic on screen. Her direction during the prayer sequences flowed expertly as the intricate choreography spoke on behalf of the emotional turmoil each member was undergoing.

Conjointly with the stunning direction, Fastvold’s cinematographer, William Rexer, focused on lighting to contrast the internal battles with Ann Lee and her journey with the Movement.

Ann Lee found love within the community with Abraham (Christopher Abbott). The scene was filled with lighter shades resembling rays shining from above. The godlike symbolism was reflected through those warm layers. She soon realised that being intimate wasn’t what she had imagined, and she didn’t feel spiritually connected to the act, which later led to the Shaker Movement adopting celibacy.

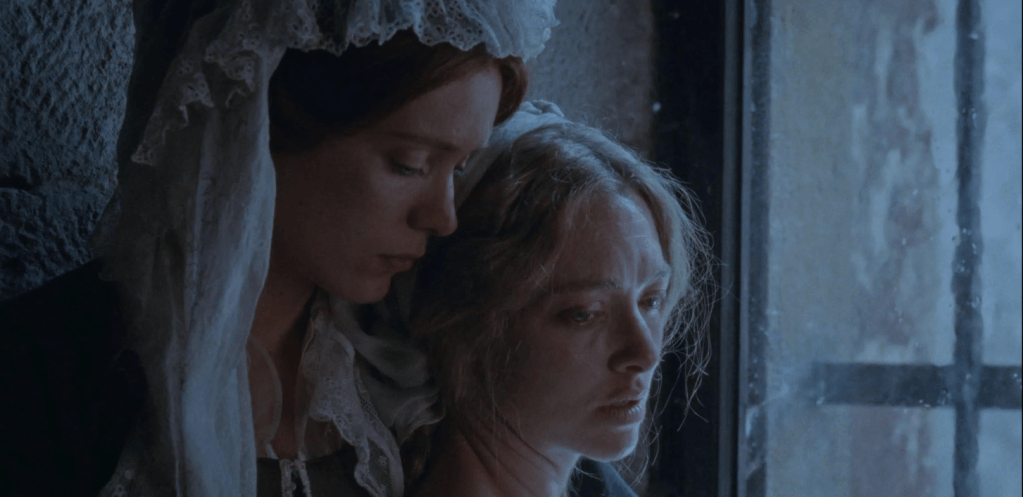

After attempting to consummate her marriage and feeling disconnected, she experienced multiple miscarriages, which contributed to Seyfried’s more raw and guttural performance in the middle of the film. The bleakness of her reality was reflected externally, and the warmth of God’s hand had turned to cold steel and gloom around her. Rexer created an atmosphere that seemed devoid of any higher power aiding Ann Lee during this devastating period.

Fastvold’s choice to barely show each child and weave in the sequences of prayer to show her connectivity to her body was genius. Seyfried conveyed the feeling of immense loss through her physical performance and delivered one of her strongest performances to date.

A woman’s connectivity to her body begins at menstruation and is further explored each decade of her life. Pregnancy is the most challenging transformation for a woman, and a miscarriage can greatly affect a woman’s mentality. Ann Lee wanted to bear children because a woman’s body was meant to do so in the eyes of God. To be unable to perform this duty made her feel empty within.

The choreography and the freedom of expression through prayer were very fluid and animalistic. You could feel the soul-crushing detachment of her miscarriages, which made her go deeper into her faith and spirituality with God. Fastvold and co-writer Brady Corbet divide the narrative into three parts: girl, woman and mother. The three sections explore the stages of a woman’s divinity and how the Shaker Movement can give that grounding force to others in the community.

Once Ann Lee made the move to the United States, the Shaker Movement became misunderstood. The Americans saw their expression of worship as satanic, conflating it with witchcraft.

Fastvold does not shy away from the violent experiences of the Shaker Movement in the third act, which resulted in Ann Lee being arrested. During Ann Lee’s incarceration, she turns to God through song. Seyfried’s angelic voice and vehement stare channelled the power of God in that cell. Again, Rexer’s cinematography shines brightly through the cell to create a symbolic insinuation that the Lord’s spirit had entered her body.

After this moment, Ann Lee was proclaimed as the female Christ by her followers. She then became Mother to all. She had performed miracles and built her own heaven on Earth just as God had shown her.

Everything up until the last thirty minutes of The Testament of Ann Lee was compelling as Seyfried gives a tour de force performance commanding every single scene. However, Fastvold and Corbet struggled to create an impactful ending to coincide with the rest of the film and the formidable life of Ann Lee.

Mona Fastvold delivers a unique retelling of the Shaker Movement with incredible choreography and lyrical expression, combined with Daniel Pemberton’s chilling score, to encapsulate the importance of a woman’s agency through faith and their resilient maternal instincts to improve anyone’s quality of life. Ann Lee had undergone hardships, but continued to help others when she could no longer help herself. It can be viewed as the ultimate selfless act to love thy neighbour.